Continuing a thread from the previous blog post, I want to continue to explore the concept of travel, if only briefly though I hope suggestively, along with related concepts and words. A partial listing… traveler, wanderer, pilgrim, stranger…

The Oxford English Dictionary conflates or interrelates two or more of these terms, indicating that the word "pilgrim" denotes "one that comes from foreign parts; a stranger", and later, "One who travels from place to place. A person on a journey; a wayfarer, a traveler; a wanderer, a sojourner" but then steers the definition more specifically towards, "One who journeys (usually a long distance) to some sacred place, as an act of religious devotion." Within this cluster of words, it appears that "stranger" may be the encompassing term. Interestingly, there is no separate entry for the word "stranger" in the American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, compiled by Calvin Watkins. But in his book on English etymology C.T. Onions forms "stranger" from the word "strange", and suggests a possible association with the word "extraneous". For some reason I like that connection; it says quite a bit about the social position of the pilgrim, the traveler, the wanderer, etc. — whether en route, or having arrived in whatever faraway or strange land. Interestingly, nor is the word "stranger" given a separate entry in An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language by Walter W. Skeat (a classic source on the subject) — though he does provide an entry for "host":

HOST (i), one who entertains guests. (F..-L.) M.E. host, haste, Chaucer, C. T. 749, 753, &c.- O.F. haste, 'an hoste, inn-keeper;' Cot. Cf. Port, hospede, a host, a guest. Lat. hospitem, ace. of hospes, (i) a host, entertainer of guests, (2) a guest. p. The base hospit- is commonly taken to be short for hosti-pit- ; where hosti- is the crude form of tostis, a guest, an enemy; see Host (2). Again, the suffix -pit- is supposed to be from Lat. potis, powerful, the old sense of the word being 'a lord ;' cf. Skt. pali, a master, governor, lord ; see Possible. y- Thus hospes = hosti-pets = guest-master, guestlord, a master of a house who receives guests. Cf. Russ. gospode, the Lord, gospodare, governor, prince ; from goste, a guest, and -pode = Skt. pali, a lord. Der. host-ess, from O.F. hostesse, 'an hostesse, Cot. ; also host-el, q. v., host-ler, q. v., hotel, q. v. ; and from the same

source, hospital, q. v., hospice, q. v., hospitable, q.v.

Note, however, how this word morphs etymologically into a set of quite different connotations, where the sense of "guest" and "enemy" share meanings, and where the word "stranger" is at last introduced:

HOST (2), an army. (F., L.) The orig. sense is 'enemy' or foreigner.' M.E. host, Chaucer, C. T. 1028; frequently spelt ost, Will, of Palerne, 1127, 1197, 3767. O. F. host,' an host, or army, a troop ;' Cot. Lat. hostem, ace. of hoslis, a stranger, an enemy ;

hence, a hostile army, host. + Russ. goste, a guest, visitor, stranger, alien. + A. S. gecst ; see Guest. Der. host-He, Cor. iii. 3. 97, from F. hostile, which from Lat. hostilis ; host-ile-ly ; host-il-i-ly, K. John, iv. 2. 247, from F. hostilite, which from Lat. ace. hostilitatem. Doublet, guest. ^f Further remarks are made in Wedgwood.

This meaning is more explicit in the entry for "guest":

GUEST, a stranger who is entertained. (E.) The u is inserted to preserve the g as hard. M. E. gest, Hampole, Pricke of Conscience, 1 374 ; alsto ght, Ancren Riwle, p. 68. A. S. gast, gest, gast ; also gist, fiest; Grein, i. 373. + Icel. gestr. + Dan. giest. + Swed. gdst. + Du. gast. + Goth, gasts. + G. gast. + Lat. hostis, a stranger, guest, enemy. p. The orig. sense appears to be that of 'enemy, whence the senses of 'stranger' and 'guest' arose. The lit. sense is 'striker.'- VGHAS, GHANS, to strike ; an extension of^GHAN, to strike. Cf. Skt. Aims, to strike, injure, desiderative of Han, to strike, wound. Der. guest-chamber, Mark, xiv. 14. From the same root, gore, verb, garlic, goad, hostile.

Returning to the OED, there is an interesting tension in the various definitions offered there, even though in the end they indicate that a "pilgrim" is one who undertakes a "pilgrimage," in the sense that we understand that term nowadays. After retailing this cluster of meanings, whether related or disparate, the OED allows that the journey undertaken by the pilgrim to a sacred place is "the prevailing sense." My feeling, however, is that there is an embedded meaning in this word and among these definitions: the wanderer who sets forth on a long journey would be seeking something, irrespective of any religious or sacred duty. Or perhaps they are seeking poetry. If so, it follows that the two broader meanings as set forth by Cid Corman ('It was to be more a pilgrimage — and in the garb of pilgrims they went — than a case of wandering scholarship…') may come together to form a single reference — the wandering scholar is as much a seeker as the pilgrim.

The OED indicates that "wander" describes the activity of one who moves about with no fixed purpose; in one definition the word is applied to the movement of a river or a stream. This is interesting as well, since rivers, while subject to change or alteration, do regularly follow relatively fixed courses toward a given destination: the ocean, a sea, a lake, or a larger river — which then subsumes and perpetuates the journey begun by the tributary stream.

I'll note that "planet", which is to say the Greek word from which the English word "planet" derives, is defined by the OED as "wanderer": "A heavenly body distinguished from the fixed stars by having an apparent motion of its own among them." — the OED glosses this as deriving from "old astron." — in reference to the pre-Copernican, or Ptolemaic, system of the universe. This is food for thought. Within that older system as channeled or filtered through Christian ideology, humans occupy the center of an ordered universe — they look up at a set of celestial spheres which have been set in motion by God, onto which the planets, the moon, the sun and the stars are affixed. Humans are assigned their own, central position on Earth (under the direct gaze of God), while the planets "wander" in the sense that they're moving around earth, as seen from below, within a geocentric system, fastened to their own respective orbs or spheres. All of this in accord with the divine plan, set in motion by the Christian God. The world-shaking revolution, and subsequent theological upheaval initiated by Copernicus and later demonstrated by Galileo and his telescope, turned this orderly and divinely regulated world system upside down. That story is well known.

My interest just now however is to persist a little longer in exploring, if only briefly and superficially (and perhaps tendentiously), this word cluster— pilgrim, traveler, wanderer, stranger — and their interrelated meanings. John Clare has a poem called 'The Tramp' which captures the randomness of movement by the social outlier:

The Tramp

He talks to none but wends his silent way,

And finds a hovel at the close of day,

Or under any hedge his house is made.

He has no calling and he owns no trade.

An old smoaked blanket arches oer his head,

A whisp of straw or stubble makes his bed.

He knows a lawless law that claims no kin

But meet and plunder on and feel no sin—

No matter where they go or where they dwell

They dally with the winds and laugh at hell."

(Excerpt From: John Clare. "Poems Chiefly from Manuscript." Apple Books)

And another poem by Clare, portraying the respectable local who stays put:

The Cottager

True as the church clock hand the hour pursues

He plods about his toils and reads the news,

And at the blacksmith's shop his hour will stand

To talk of "Lunun" as a foreign land.

For from his cottage door in peace or strife

He neer went fifty miles in all his life.

His knowledge with old notions still combined

Is twenty years behind the march of mind.

He views new knowledge with suspicious eyes

And thinks it blasphemy to be so wise.

(Excerpt From: John Clare. "Poems Chiefly from Manuscript." Apple Books)

"Dally with the winds and laugh at hell," or "plods about his toils and reads the news." Pick your poison. There is a poem in VEII And Other Poems (Carcanet, 2021) the most recent book by the English poet Robert Wells, which I think captures the complementary tension between making toward a goal, or being at swim in the universal flux. The poem is called 'Loggerhead':

Type of a courage to which the heart, intent

On its own journey, answers:

the sea-turtle,

Unwieldy, solitary, tilted aslant,

Ferrying itself along through the green swell.

Wells explains in a note that,

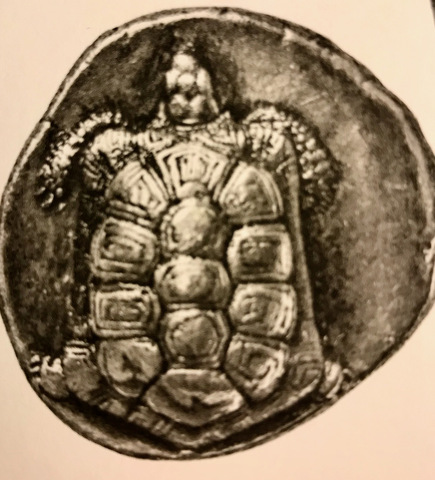

I was thinking of seventeenth-century emblem poems. But the turtle is a real one, seen off the island of Melos some forty years ago. A turtle also figures on the coins of Aegina, the earliest to be minted in Europe.

The heart 'intent on its own journey' may be purposeful, or may be obeying a primitive, migratory instinct. Or both. But the turtle is a wonderful emblem of travel, on account of its slowness and deliberateness, and in the poem, the turtle is the embodiment of contraries -- experiencing a purposeful enthrallment. William Blake: "without contraries, there is no progression." And so the loggerhead ferries itself along. I love the connection Wells makes to coins — which portend travel undertaken by merchants, and subsequent trading activity among strangers. So too with fieldwork — I understood that my position as outsider, someone who would soon move on, never returning, facilitated a more robust exchange of information, and disclosures.

With this I feel I'm moving toward concluding this one post, but not completion of the larger subject, however. During the years I was actively doing fieldwork, my intention in every case was to fulfill the contractual obligations I'd been party to. But I also sought ways to dissociate myself from any overt purpose with that travel; to give myself over to travel per se. Around that time I read an essay by Gary Snyder in a book I'd found, browsing the shelves of the Carnegie Library in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh. Snyder wrote about a Japanese poet who practiced a traditional form of poetry that involved walking, rather than writing. I right away understood that. In his introduction to For All My Walking, a book of translations of haiku and diary excerpts of Taneda Santōka, Burton Watson suggests that for Santōka,

The two activities of walking and composing haiku seemed to complement each other, and his many journeys, lonely and wearisome as they were, gave him a sense of fulfillment that he could gain in no other way.

The seamlessness between the two activities was well expressed by Santōka in a haiku:

I go on walking

higan lilies

Go on blooming

As a longtime walker, traveler, and sometime wanderer, this struck home. Rhythm, open sky, epiphany — pathways to poetry; words on the page superfluous? Loggerhead; with a shake of Blake.